Officiating under pressure: Analysing the match defining Lions decision

BY KEVIN CARPENTER, PRINCIPAL (@KevSportsLaw)

On Saturday 8th July 2017, with two minutes left to go in the match, the score at 15-15, and with the series tied at one-all, French referee Mr. Romain Poite made the most high pressured and important decision of his refereeing career to date, and one of the most controversial decisions in rugby union history.

Having awarded a kickable penalty to New Zealand for the Lions number 16 Ken Owens playing the ball from an offside position having been knocked-on (when a player loses possession of the ball and it goes forward, or when a player hits the ball forward with the hand or arm) by his teammate Liam Williams, Mr. Poite reversed his decision to accidental offside and awarded a scrum to New Zealand from which they did not score any points. Both the match and the series ended in a draw. Here is how the incident unfolded:

Having been a sports lawyer for six years (and counting), played rugby union for five years, been a rugby union referee (at the amateur level) for the past three years, and previous to that a football referee for seven years up to the semi-professional level, I feel I am in a good position to provide an insight into the decision that was made.

The key laws

The first issue that is not under conjecture is that Ken Owens was in front of Liam Williams, and therefore in an offside position as per the definition in Law 11 (Offside and Onside in General Play):

Consequently, the two laws that Mr. Poite had to consider, and decide which to apply, in relation to the incident were: Law 11.6 (Accidental offside) and Law 11.7 (Offside after a knock-on):

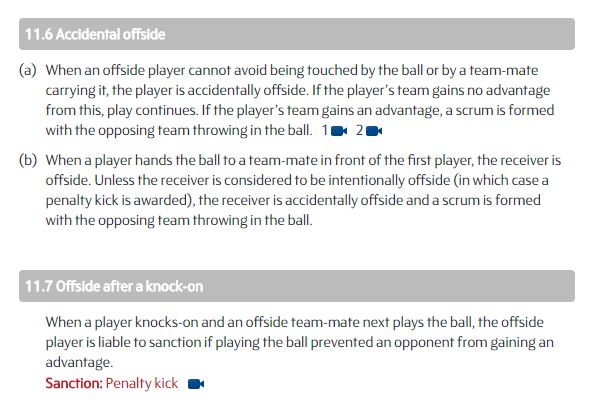

Given the wording of the relevant Laws, I created this decision tree which reflects what a referee’s thought process should be in this situation:

Full speed analysis

At full speed during the match as I was watching on television, and the view of Mr. Poite initially, it certainly appeared as though:

- the ball had been knocked-on by Liam Williams;

- there was a reflex reaction by Ken Owens in initially catching the ball, although he then dropped the ball, he still “played the ball”; and

- Owens also prevented an opponent from gaining an advantage because there was a New Zealand player directly behind him ready to take the ball.

Therefore, at full speed Mr. Poite correctly identified an offence had occurred under Law 11.7 and awarded New Zealand a penalty kick.

Role of the TMO

One of the areas that World Rugby (the international federation for rugby union) has been looking to clamp down on in recent years for safety reasons is players being tackled in the air with their feet off the ground. Having awarded the penalty kick Mr. Poite asked the for opinion of the Television Match Official (TMO) as to whether there had been any foul play when All Blacks captain Kieran Read attempted to challenge for the ball with Liam Williams.

There are only a narrow set of circumstances in which the TMO can intervene of their own volition or be asked to do so by the referee. Given both the Law and the TMO Protocol, Mr. Poite can only have gone to the TMO to ask whether there had been any potential foul play, not whether there had been an offence under Law 11. Indeed, this is what the TMO George Ayoub reported back to Mr. Poite about.

There are only a narrow set of circumstances in which the TMO can intervene of their own volition or be asked to do so by the referee. Given both the Law and the TMO Protocol, Mr. Poite can only have gone to the TMO to ask whether there had been any potential foul play, not whether there had been an offence under Law 11. Indeed, this is what the TMO George Ayoub reported back to Mr. Poite about.

Where there are potential acts of foul play, the on-field match officials are permitted to view the same replays as the TMO is looking at on the in-stadium screens. This is what Mr. Poite appeared to do. During this period, having confirmed with the TMO that there was no foul play as it was a fair challenge by Kieran Read, Mr. Poite then walked back to the place where the incident occurred to talk to the two captains, at which point he communicated to them that he had changed his decision to be accidental offside.

The Joubert incident

Before moving on to discuss the incident with the benefit of slow motion and replay video evidence, many people have suggested that Mr. Poite’s change of mind in Saturday’s match was his ‘Craig Joubert moment’. The reason for this is that during the 2015 Rugby World Cup in the quarter-final game between Australia and Scotland, in the 78th minute, with Scotland 2 points ahead, Mr. Joubert awarded a penalty to Australia under Law 11.7, which they converted and won the match by 1 point.

There was outrage at the time because replays appeared to suggest that the final touch had actually come off an Australian player, before being caught by the Scottish player in an offside position. Therefore, a scrum, and not a penalty, should have been awarded to Australia.

Many questioned why Mr. Joubert did not ask for assistance from the TMO, however in a press statement made during tournament, World Rugby had made it clear that the TMO was only available to the referees in certain limited circumstances, as already stated above, and therefore Mr. Joubert could not consult the TMO and indeed the TMO could not intervene to award the correct decision.

Replay & slow motion analysis

Although the majority of people quite rightly believe the more evidence and angles the better, you have to be mindful the fact that repeated viewings of the same incident, especially at the slower speeds, can distort the ‘ordinary view’ of an incident.

Starting at the top of the decision tree, having watched the replay there is some doubt as to whether there was in fact a knock-on by Liam Williams at all in attempting to catch the ball from the kick-off. Therefore, some have suggested there was no knock-on at all and therefore it was correct to award a scrum to New Zealand.

This is where the location and angle at which the TV cameras are placed distorts reality. I took part in a practical exercise on this point when a football match official, ith a former World Cup final assistant referee showed how even being half a foot out of what the parallel is can change your view of what is forward or not.

If we proceed on the basis that there was a knock-on, did the offside player Ken Owens “play the ball”? Few would disagree that in catching the ball Ken Owens was acting instinctively and not with any intent. However, it does not appear that intent is a relevant consideration when it comes to whether the ball has been played. In catching the ball and then releasing it, in my opinion he has clearly played the ball. The reaction of Ken Owens, and the legitimate expectation of not only the New Zealand players but also the body language of the Lions players, suggested that they thought he had played the ball and therefore committed an offence which a sanction of a penalty kick.

In doing so, Owens also prevented the New Zealand player from gaining an advantage by taking possession of the ball and running towards the try line. What is interesting is that Mr. Poite did not play advantage, despite the fact that having dropped the ball, the New Zealand player had actually collected it and begun to attack. In having blown his whistle, a little in haste before considering the possibility of an advantage, Mr. Poite had then then placed himself in a very difficult position and had to award a penalty.

Communication

One of the things which rugby match officials are often praised for is their clear communication both between themselves and with the players. However, on this occasion, Mr. Poite was found wanting.

In his discussions with the TMO, he never once raised the possibility that it might be a case of accidental offside, in fact his words to the TMO were, “Are you happy for the knock on. The challenge in the air was fair. Penalty kick against 16 red in front?” The TMO replied, “Yes I am”.

In the period from initially awarding the penalty, to then reversing his decision, the British and Irish Lions’ captain Sam Warburton planted the seed of doubt in Mr. Poite’s mind that it was a case of accidental offside and should only be sanctioned with a scrum to New Zealand. More of this below.

When walking back to the place where the offence was committed, it appears that Mr. Poite had an intervention from his fellow French touch judge Jerome Garces. It is not apparent what Mr. Garces said over the communication system but Mr. Poite indicated his verbal agreement with it.

Mr. Poite’s next communication was directed to the two captains, who had heard his discussions with the TMO, where he stated that 16 red did not “play deliberately the ball and it was an accidental offside…a scrum for black.” The word “deliberately” does not appear in either Law 11.6 or 11.7 and therefore we can only speculate, in looking at the decision tree, that this would fall outside the definition of “playing the ball”, and therefore a scrum was awarded. It was incorrect for Mr. Poite to use the phrase “accidental offside” in that situation, but at the same time we must remember that English is not his first language.

Pressure

Despite having been a top level international referee for over a decade, objectively Saturday’s game was Mr. Poite’s biggest game of his career to date. Indeed in the lead up to the final test, many were saying that it was a bigger occasion than a World Cup final. Despite having refereed a number of high profile international and club fixtures previously, in my opinion the occasion did get to Mr. Poite, in the final 10 minutes or so especially, where he was reluctant to award a penalty kick to either team which would ultimately decide the game.

For instance, there was more than one occasion where he did not award penalties to the dominant scrum who were clearly going forward at quite a pace. This is very unlike Mr. Poite and contrasts significantly with his performance in the final test of the previous Lions tour in Australia in 2013.

As mentioned above, Mr. Poite also allowed himself to be influenced during the key incident by the Lions captain Sam Warburton. This was very astute behaviour by Sam Warburton, and his relationship and manner with referees is one of the reasons why he is a trusted captain of long standing for Lions head coach Warren Gatland.

Final remarks

This analysis is not meant to be a criticism of Mr. Poite, rather it is meant to be an analysis of what will be one the most talked about decisions in rugby history and to give those not of an officiating or sports law background some insight into why Mr. Poite may have took the actions he did.

Despite all of the analysis which has taken place after the match, some of which I have set out in this post, as a match official myself I still come back to what looked like had occurred at full speed during the heat of the moment. Therefore, to me, Mr. Poite should have stuck with his original decision and awarded a penalty kick to New Zealand.

There are two final points I think it is worth making:

- The role of the TMO in such situations needs to be discussed by the people responsible for the Laws of the Game and officiating because there is a delicate balance to be had between too much intervention by the TMO slowing the game down and yet ensuring that correct decisions are made. As with the Craig Joubert incident which took place 2 years ago, currently the TMO’s hands are still tied when such an incident as that in the 3rd Lions test arises.

- The same people also need to consider the wording of Law 11 because despite me having been able to create a decision tree, this was far from straightforward (and open to challenge), and in my opinion there needs to be some element of intention introduced into the Law if a penalty kick is considered to be an appropriate sanction. Although of course this is fraught with danger as we have seen in other sports such as football (i.e. with handball), and therefore a simpler solution may be to simply award a scrum to the opposition wherever a player in an offside position plays the ball, whether it be deliberate or not.

PUBLISHED 12 JULY 2017